I am, by nature, an optimist. For various reasons this seems to have become slightly unfashionable lately, so I was pleased, during my usual adirectional reading/youtube trawling, to find something new to be optimistic about. It turns out that when a group is making a decision it can be useful for a proportion of its members to be completely ignorant of the correct response. Merely by listening to their peers these uninformed individuals can increase the effectiveness of decision making.

Well, isn’t that nice! Personally, I find myself almost completely ignorant about almost completely everything so it’s good to know I can still be of some use. In fact, we’re all very good at being ignorant. It takes a hell of a lot of effort to escape this very natural state, and even when actively trying to build an expertise – say by doing a PhD - I find the information only takes a few years to come slipping back out of my memory (though it comes back quicker the second time over).

The source of this exciting finding was a 2011 paper (Couzin et al., Science, 2011) that studied group decision making in freshwater shoaling fish and related models. These fish swim around in tight groupings and, without apparent recourse to a leader, somehow come to communal decisions about which way to swim next. It turns out their shoaling behaviour can be nicely modelled by assuming that the fish align their direction with their neighbours’, while also maintaining a small personal bubble. Some individuals will have an idea of which way to go and these fish are partly influenced by their neighbours and partly by their internal drive. If there is consensus among the ‘leading’ fish – those with a direction preference - these dynamics ensure the group will happily follow them, creating coherent group dynamics that makes use of their members’ knowledge.

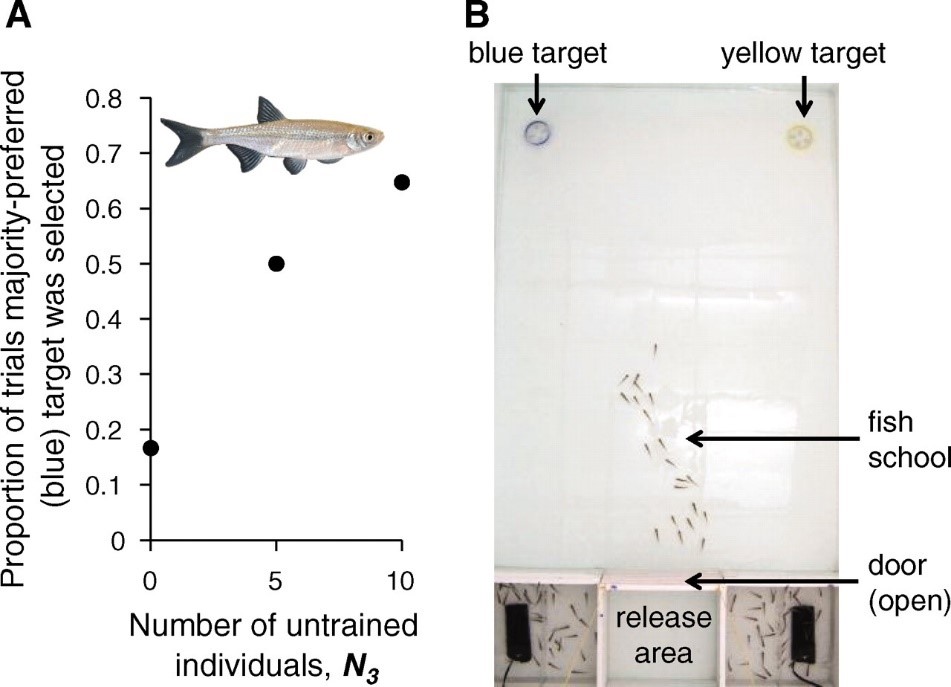

The situation becomes more difficult if the group contains multiple opinions. The authors tested a two-choice task in which opinionated fish are trained to swim towards either a blue or yellow target, and the yellow-preferring fish are trained to have a stronger preference. A group of 6 blue-preferring, 5 yellow-preferring, and variable numbers of naïve fish are then recruited and left to come to a consensus decision. Will they follow the vocal minority to yellow, or the quite majority towards blue?

Well, it turns out that when there are no ignorant fish the yellow minority wins, but as the number of ignorant fish increases the group prefers the majority-supported blue choice. This behaviour was found in a wide variety of systems that possessed two characteristics:

Now, the temptation to jump from tiny fish to sweeping claims about society is huge; we are after all just animals heavily influenced by our neighbours. But anthropomorphising is a dangerous business, and, unlike the initial media coverage, I will try to resist its most egregious forms. However, I can’t help but look at similarities between ignorant crowds of fish and humans, if only to pin down the useful form of ignorance.

A striking example of decision making by ignorant crowds (at least for those of us living in Common Law countries like the UK, US, and Canada) are jury trials, where 12 average-Joe citizens with zero legal knowledge are placed in court to determine guilt or innocence. This form of trial is almost 1000 years old and when it was first introduced the leading alternative was trial by ordeal. Examples of trial by ordeal include making the defendant walk 3 metres holding red-hot iron and examining their wounds three days later, if they’ve festered God has shown the defendant’s guilt. You can see why jury trials took off.

Yet despite their complete lack of legal know-how, studies have found that jurors tend to take their responsibilities seriously, sift reasonably through the evidence, and group discussions draw on the experience of all members to inform decisions. Indeed, in a study of 8000 cases in the Australian legal system the jury and the judge agreed on the verdict in 80% of cases. And even when judge and jury don’t agree it’s not clear who’s correct! There is a tradition of Jury Equity in which an innocent verdict is passed regardless of the facts of the case, simply because the jury felt the law was unjust. In the UK this has been used to acquit both peace activists and medical cannabis users despite their clear breaches of the law.

Similar ideas are at work in the hip new legislative tool all the cool kids are talking about, citizens’ assemblies. The basic scheme is a group of randomly selected citizens gather each weekend for a few weeks to discuss a thorny policy issue. They are given information by experts about all sides of the argument and some possible solutions, and then they debate the issue between themselves, before concluding with a series of recommendations. This has been credited with breaking the decades-long deadlock surrounding abortion in Ireland, where the findings of a citizens’ assembly led to a referendum and the repeal of the abortion law, and they’ve been used to discuss issues such as the climate crisis in the UK. During an otherwise bleak period for the reputation of representative democracy this is an exciting possibility.

Now, this is all interesting, ‘isn’t it great to be so incredibly uninformed!’, but there are of course caveats. Somebody must be informed; else our group of fish will just mill around endlessly. Further, it’s not obvious that the fish came to the correct decision: who’s to say that those who are more vocal shouldn’t be listened to more, perhaps they are more correct?

But I think we can still draw some lessons from this. In both fish and citizens, it only works when the uninformed individuals are somehow paying attention, either through aligning their swimming direction or through reasoned debate between jury members. When we find ourselves ignorant, as we almost always will, we should foremost be honest about it and listen. On the other hand, those that have expertise must speak up, putting in effort to persuade their peers rather than simply follow the flow, while respecting the ability of a group of well-meaning individuals to come to better consensus decisions than any mystic seer.

This is almost certainly a collection of mindless platitudes; but in daily life platitudes can be of great importance. As evidence I would present Sama’s group discussions at Imbizo, in which each member spends 10 minutes discussing a problem they’ve been having while the listeners ask only curious questions. In this way the listeners are displaying a certain sort of ignorance, without intent beyond understanding. I can attest myself to the power of this technique for working through your own thoughts, and humbly propose that this can be understood through an analogy with a headstrong fish and his well-meaning chums.

Or at least, that’s what I concluded, but I’m no expert, perhaps you think I’m full of shit! Feel free to let us know at youmustbekidding@imbizan.com.